The word canon comes from the Greek kanon (κανων), meaning “rule.” The canon of Scripture thus refers to the rule of Scripture, identifying what is Scripture. But the issue of canon actually deals with two questions:

- Which books belong in the Bible?

- And what should be the order of these books?

The Old Testament and New Testament (from here on OT and NT) are usually dealt with separately in answering these questions, as the two testaments were written hundreds of years apart from one another. (The OT was likely finished by the 5th century B.C., and the NT was written in its entirety in the 1st century A.D.) Here we will only address the OT canon. But for now, let it be said that all Christians agree on which books belong in the NT and their order (Gospels, Acts, and Epistles).

Which Books Belong in the Old Testament?

The best way to address the question of which books belong in the OT is to examine the three-fold division of the OT used by the Jews of Jesus’ day—the Law, the Prophets, and the Writings. We know that Jesus Himself used this division because of Luke 24:44, where Jesus told the two men on the road to Emmaus,

These are my words that I spoke to you while I saw still with you, that everything written about me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms must be fulfilled.

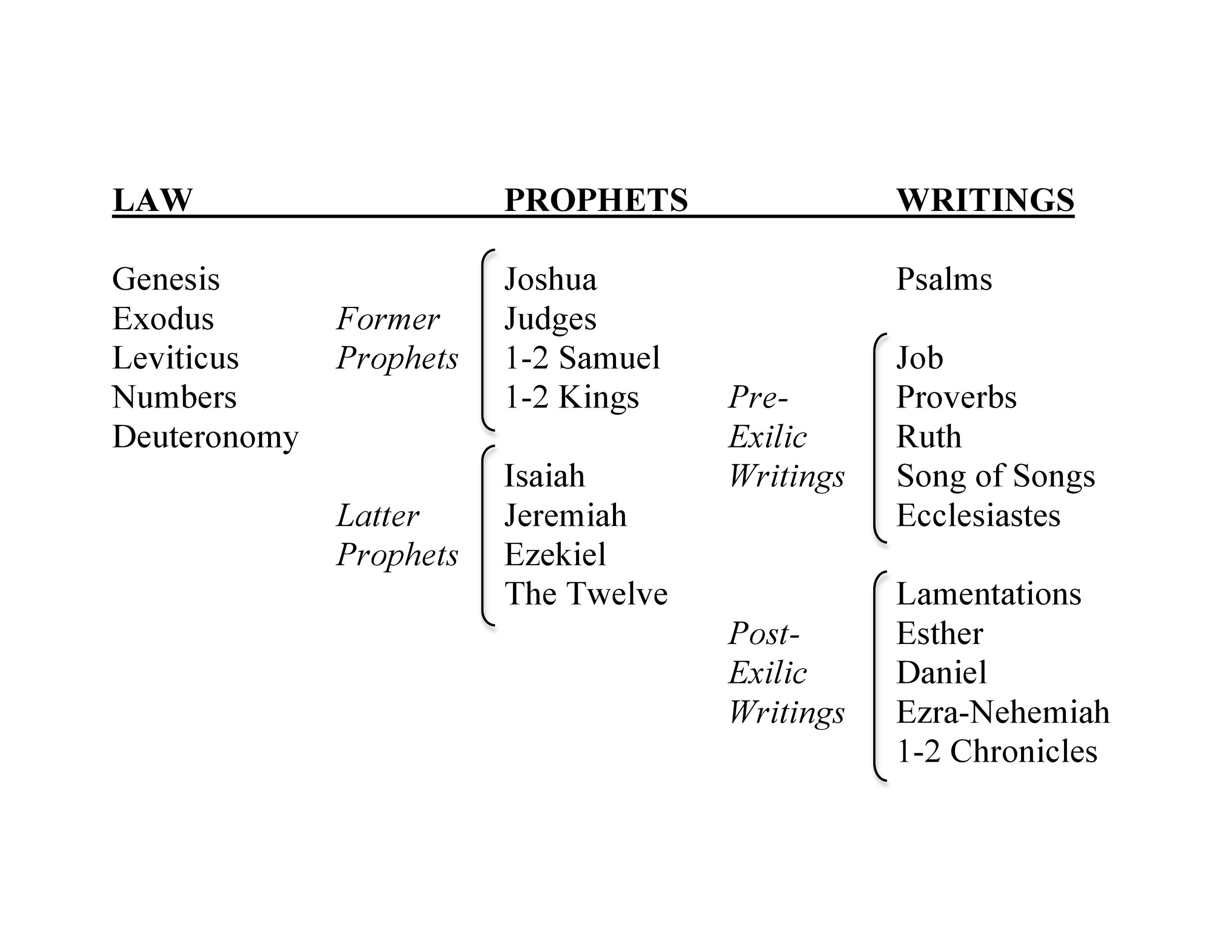

This is a way of saying that the OT points to Christ, but it is also an example of Jesus’ use of the three-fold division of the OT. Jesus mentions the Law of Moses (Hebrew Torah means “law” or “instruction”), which is the covenant law laid out by Moses. The Law includes the books Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Jesus then mentions the Prophets, the covenant history that called Israel back to the law. The Prophets include the books Joshua, Judges, 1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the Twelve (the Minor Prophets). Jesus then mentions Psalms as a synecdoche (a part representing the whole) for the Writings, as Psalms stands at the beginning of the Writings and is the largest and most famous book in this section. The Writings are about covenant life, and this section includes Psalms, Job, Proverbs, Ruth, Song of Songs, Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, Daniel, Ezra-Nehemiah, and 1-2 Chronicles. The Prophets and Writings can be further subdivided into former & latter prophets and pre-exilic & post-exilic writings (as seen below).

Modern Jews still use this division and refer to the Hebrew OT as the Tanakh, which is made up of the first letters of the Hebrew words Torah (Law), Neviim (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). (The order of the Writings can vary.) The order of the Hebrew canon is thus different from that of our English Bibles, and there are good reasons we should follow the Hebrew order. (There will be more on the order of the OT books in another article.)

These were the 24 OT books accepted by Jews in Jesus’ day, and these are the books the early church accepted. The earliest Christian list of the OT books is from c. 170 A.D. by Melito, bishop of Sardis, who included all the OT books except Esther and made no reference to the Apocrypha. Athanasius in his Paschal Letter of 367 A.D. listed all the books of our present NT and OT except Esther (there was likely some doubt due to Esther not mentioning God). He mentioned some Apocryphal books but said they are “not indeed included in the Canon, but appointed to be read by those who newly join us, and who wish for instruction in the word of godliness.”

What About the Apocrypha?

Unfortunately, there is not complete agreement among Christians today regarding which books belong in the OT, demonstrated in that the modern Roman Catholic Church includes extra books known as the Apocrypha (which means “hidden writings”). These are inter-testamental books written sometime between the 3rd through the 1st centuries B.C. They were written in Greek and were included in the Septuagint (the Greek version of the Hebrew OT, translated sometime between the 4th and 1st centuries B.C.) and were later included in the Latin Vulgate—which led to confusion over the Apocrypha’s place in the canon. The Apocrypha books are Tobit, Judith, additions to Esther, Wisdom of Solomon, Ecclesiasticus, Baruch, Epistle of Jeremiah, additions to Daniel, and 1-2 Maccabees. Protestants believe they are useful as historical books, but they reject the Apocrypha as canonical for several reasons:

- The Jews of Jesus’ day did not consider the Apocrypha canonical. The Jewish three-fold division of the OT leaves no room for the Apocrypha. Even Josephus (37–100 A.D.) said the Apocrypha are “not . . . worthy of equal credit” with the OT books.

- The NT authors never cite the Apocrypha as Scripture. Hebrews 11:35 seems to reference the Apocrypha but does not cite it as the authoritative Word of God.

- The early church considered the Apocrypha deutero-canonical (“secondary canon”). Jerome, who translated the Latin Vulgate in 404 A.D., said the Apocrypha were not “books of the canon” but “books of the church.”

- The Roman Catholic Church did not officially declare the Apocrypha as Scripture until the Council of Trent in 1546 A.D. This is contrary to the much earlier statements of Jerome and Athanasius.

For these reasons, we should not consider the Apocrypha as the inspired Word of God. The Apocryphal books may be helpful as historical books, but we should not put them on par with the Law, Prophets, and Writings that make up the Old Testament.